Germany is fast approaching the 30thanniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, which took the country and the world by surprise on November 9, 1989 (for more on how this actually came about, stay tuned for the book!)

Unbeknownst to the rest of the world, for a tiny East German village 130 miles northwest of Berlin, November 8, 1989 was an equally momentous day: On this day, the residents of Rüterberg (population 140) declared their village an independent republic– they basically seceded from the GDR (East Germany).

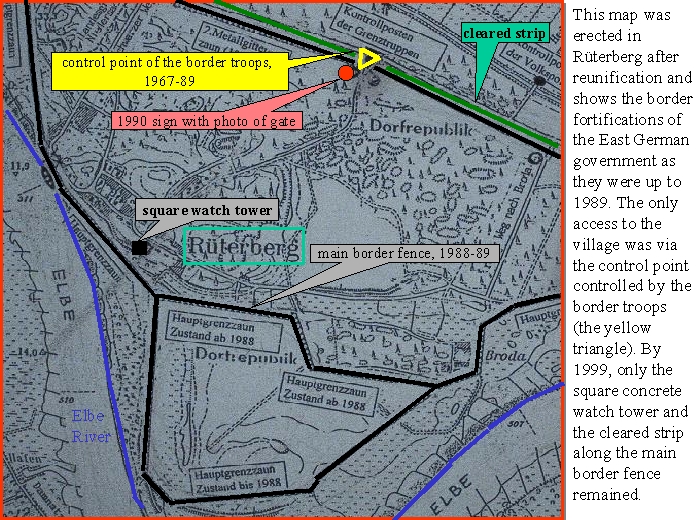

Rüterberg is located on the shore of the River Elbe, right in the 70-mile stretch of the river that doubled as a de facto international border after the declaration of the two German states in the wake of World War II. As you probably know by now, this border – the Iron Curtain – was one of the most fortified borders in the world. For a quick geographic refresher of where that border was, see this map which, incidentally, also shows you the route of my border expedition by bicycle and on foot.

Even residents of the 500 meter highly restricted zone adjacent to the border could only cross into the rest of East Germany through a checkpoint (and back into the so-called “protective zone”) with their specially stamped ID. Conversely, visitors from the rest of East Germany had to apply for a special permit and were limited to first-degree relatives. Rüterberg was not only cut off from the Elbe and “the West” by the Iron Curtain, but also from the rest of East Germany by an additional fence. The Rüterbergers had thus been doubly fenced in, held prisoner not only in their own country but also in their tiny village.

In today’s excerpt from Chapter 8, join me on a visit with Meinhard Schmechel, who was Rüterberg’s mayor from 1981 to 2004. Find out what life was like in the fenced-in village and what happened in Rüterberg on November 8, 1989.

Meinhard Schmechel looked to be around seventy, stout, in a checkered shirt and jeans. Even while we were still shaking hands, something about him made me think of him as a Gemütsmensch– a low-drama person, someone who does not lose his calm easily. Gelassen. Probably a good disposition for putting up with a fence around one’s village, and, on top of that, being mayor of that village and having to deal with border and Stasi officials.

He led me to the living room of his red-brick house and introduced me to his wife, who was just shaking a bad cold and resting on the sofa. Coffee cups and a bowl of cookies were already on the table. Where there is Kaffeetrinken, I thought, the world is still in Ordnung. Drinking coffee is, of course, not limited to Germans, but I still think of the afternoon ritual of taking time to sit together and have a conversation over coffee and pastry, at a table set with “real” cups and plates, as a little German secret.

“So that gate I just rode by, the one by the levee – is that the original gate where you had to have your IDs checked to enter the rest of the GDR? Was that the main access to Rüterberg?” I asked.

“Actually there was just a small gate there by the levee, only for border guards,” Herr Schmechel said. “The main gate was on the other side of Rüterberg. That was the only place we residents could leave or enter the village during GDR times.”

“So why was only Rüterberg fenced in like that?” I asked, “when the other villages in the Schutzstreifen (protective zone) weren’t?”

“Take a look at a map. Rüterberg sits in a special location: The Elbe makes this big bend here; we basically had ‘the West’ surrounding us on three sides.” I thought of Strachau, which was also sitting on the edge of a riverbend. But Rüterberg’s riverbend was more pronounced, more like a peninsula. I also knew that the border regime had not been consistent in each segment of its 870 miles. Still, it seemed that the Rüterbergers had suffered disproportionately. (In my research for the book, I discovered yet another reason for Rüterberg “special treatment” by the GDR – stay tuned for Chapter 9)

“And what was that like in everyday life, to be fenced in?”

“It was the worst. The gate was locked from11 p.m. to 5 a.m. If someone from the village forgot their ID, that was a catastrophe. If you left home without money, that was no big deal – at the gas station and so on they would just write down what you owed, but if you didn’t have your ID, you couldn’t get in or out of the village. You couldn’t get to work that day, because the bus couldn’t wait for you to go back and get your ID.”

“What if someone needed a doctor during the night?” I asked.

“Nothing you could do, the doctor could not get in and we could not get out. When my daughter’s birth came close, I kept a pair of wire cutters in my car just in case. I would have cut the fence open if it had come to that.”

“Did anyone ever escape from here?”

“Oh yes, there was a young man whose dream was to be a sailor. In school, he had had a 4 [a poor grade] in civics class, and so the party decided he was not trustworthy and they put an end to that dream. So he went rüber (“across,” to the West). That was in 1972. His father was fired immediately; he had been a commander with the border troops. Shortly after that, the whole family was expelled from the border area. Oh, and a cow swam rüber once. You may have read about that, it made a big splash in the media.”

This was the first I had heard about the cow’s “escape” – apparently I hadn’t followed German news closely enough.

“How did the young man get across?”

“He waited until the border guards had gone past, and then he got down to the river and waited for a West German customs boat to come back from its daily patrol. If you lived here, you knew when the border guards made their rounds and when the boats on the Elbe passed by. He got their attention and they picked him up.”

“And nobody saw it?”

“Some people did, but they closed their doors quickly. Of course we were supposed to report anything like that, but it was better not to know anything. The Stasi made a huge production about it of course.”

“Did he ever find out what happened to his family?” I asked.

“Yes, he did. It was very difficult for him, and of course for them. I don’t think they ever talked to each other again. He also found out that the Stasi had spied on him for four years in the West after his escape.”

I could feel the heaviness descending on me again. The constant risk that a careless word or someone else’s escape could put your life into a tailspin. For those who did escape, could they ever truly feel like they were starting a new life in the West?

Rüterberg had had 300 residents when the border had been built up starting in 1952. By 1989 only 140 were left. Some had died, but twenty-two families had been forcibly evicted. “My in-laws were on the list, too, but they got wind of the plans and went to the party chair,” Herr Schmechel said. “For some reason, they were then allowed to stay – maybe because they didn’t escape.”

The callousness of the evictions and the constant surveillance and regimentation had grated on the Rüterbergers. And despite their isolation from the rest of East Germany, they were well aware of the rising discontent that was spreading across the country in 1989: “We had Western TV, after all.” Resentment was ratcheting up, especially when a construction crew had come to fortify the fences around Rüterberg in 1988.

“You’ve heard the name Hans Rasenberger, right?” Herr Schmechel asked. I had. Hans Rasenberger was the retired master tailor who had come up with the proposal to declare Rüterberg a republic.

“That was highly emotional,” Herr Schmechel said, “You have to imagine that all the higher-ups were there, the district supervisor for the Department of the Interior, the border patrol supervisor, the district police commander…We [Rüterberg residents] asked them to get rid of the gate. And they said no, we are not doing that. And some people were getting really upset. The police commander, when I saw him later, he said to me that he had been afraid that things would spin out of control.“

It was only dawning on me now that the Rüterbergers’ demand that evening had not even been directed at the border between East and West Germany. All they had asked for was permission to access the rest of East Germany freely, without border controls. Still, for the “higher-ups” that was asking too much.

“And that’s when Hans stood up and said, ‘Let’s declare Rüterberg a village republic. That way we can make our own laws. Everyone in agreement, raise your hand.’ Everyone from the village raised their hand, including our village policeman.

“We really didn’t know what would happen to us after that. The next day we were waiting to see whether they would come and pick us up. And there was a phone call from Berlin – the whole thing had gone up to the highest levels right away, and they asked if we were standing by our village republic. I said yes, we are. And then later that evening, the Berlin Wall fell and the border opened. But of course we didn’t know that. Nobody did.

“And you know what was crazy? The guards at the village gate continued to check papers for several more days. Even though the border between East and West Germany had become meaningless, GDR citizens from outside the Schutzstreifencould still not come to Rüterberg, and we could still not cross freely into the remainder of East Germany.”

Stay tuned for next week’s installment about the Mr. and Mrs. Schmechel’s “border violation.” What would you have done if you had heard somebody scream for his life on the other side of the Iron Curtain?

Fascinating post Kerstin. I hadn’t known about this double fenced in town in East Germany. Kind people trapped by a brutal system. My hope is that we can learn from this history and create a system that’s primary purpose is to be a benefit for the people living under it.

[…] border that was doubly fenced-in. If you missed last week’s posting on why, you can catch up here. In today’s excerpt, find out about the border violation committed by the former mayor and […]

Bravo, Kerstin. Very well written. I love that you are highlighting small acts of courage in the story of the German border. I think that those are important to remember and also inspiring to consider those opportunities in our own lives.