The next few posts will be about my visits with people in Kella, population plus minus 500. When Germany was divided after WWII, Kella ended up in the 500-meter Schutzstreifen (“protective zone”) right next to the border strip, which meant that its residents had to put up with considerable restrictions on everyday life, imposed by the East German government.

One of my goals with this “border project” is to show the complexity of life in the GDR and not reduce it to all Stasi and oppression without minimizing their very real and often devastating impacts on people’s lives. But people also had everyday lives that included family, friends, work, hobbies, faith, and they often pushed the envelope of the restrictions their government imposed on them. I was fortunate to connect with several of Kella’s residents and hear firsthand about their experience in the East German borderland.

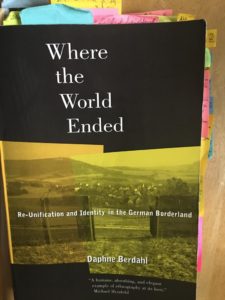

The glorious downhill ride to the Werra valley had not only ground down my brake pads, it had also made me wary of the climb back up that kind of elevation difference – which I would have to do if I wanted to get to Kella, the border village the American anthropologist Daphne Berdahl had written about in her book, Where the World Ended. Berdahl had lived in Kella (population 500) for two years soon after East and West Germany reunited. Her book had laid the groundwork for my understanding of life in the East German borderland – and for how, as the physical border disappeared, a cultural boundary between East and West had lived on and, to some extent, been created.

Through her descriptions, I had begun to take an interest in the village and the lives of its people, and the idea to visit and try to connect with some of them had taken shape. Sadly, Berdahl herself had died of cancer in 2007, aged only 42, before I even became aware of her book. But I had been able to get a hold of Kella’s mayor during a break from my expedition, and he had put me in touch with a woman who had been good friends with Daphne.

Without a moment’s hesitation, Anna Biermann had offered to meet me, show me around Kella, and introduce me to others who had known Daphne. And when I had called to confirm the visit, she had also offered to pick me up in Eschwege, a town in the Werra valley. I had accepted her offer gladly: Besides the challenge my leg muscles would have faced on the way up to Kella, I feared that the brake pads might be too far gone to allow me to control the bike on the way back down. I would have to find a bike shop before too long.

The border had run alongside and just over the tops of the hills that encircled Kella on three sides. Eschwege, the nearest larger town, was only seven kilometers away but had become increasingly unreachable with each round of border fortification. I knew from Daphne’s book that this process had caused deep gashes in the social fabric of lives on both sides: the two towns had been closely connected by economic and family ties for generations. Anna’s family, I was about to learn, had its own such wound.

Now, in Anna’s car, I could hear the engine starting to labor as the road climbed ever higher. Anna downshifted again, then turned off the road into a parking area just past the crest of the hill. “This is Braunrode,” she said; then explained that this spot had served as a viewpoint from the West during the division. Western relatives had come to wave at their loved ones in Kella from here – the closest they could come, since Westerners could not get permits for the Schutzstreifen. Sometimes tour buses had come here for a glimpse of the border strip and the GDR. During those times, the road had ended just past the parking area in a tall pile of debris and wire fencing, Anna explained. Kellans could see when someone was waving from Braunrode, but waving back was strictly prohibited. Still, villagers had come up with all kinds of creative ways to send covert signals across the border: “Some people would shake feather blankets or jackets out their west-facing windows; I would hang towels and cloth diapers out to dry and then discreetly wave them.”

Stay tuned about more from Anna and other Kella residents next week…

This is such an interesting project, Kerstin. Thanks for blogging!

And thank you for reading, Nancy!

So cool that you were able to meet and talk with the author’s good friend, you’ve really done some wonderful research. I can imagine people secretly waving back across the border while drying their laundry.