As Kai goes on to fill in the picture for me, I realize that what made the resolution for the Green Belt so effective was a chain of developments that sounded almost providential. Kai Frobel himself uses the expression glückliche Fügung, the coming together of auspicious circumstances. What becomes quite clear to me, too, is the central role he played in all of this.

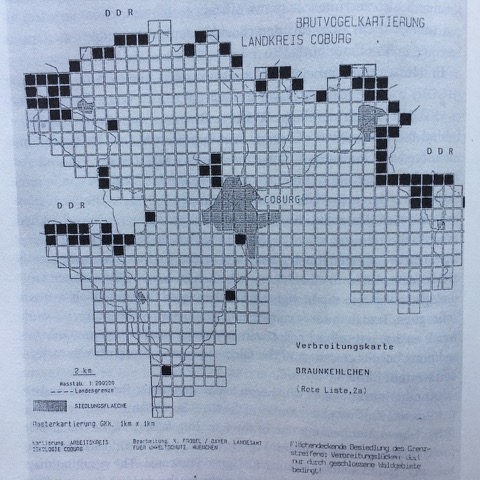

Not only was there his science project in 1977, which was published in a scientific journal the following year when he was seventeen. Kai had also led a youth conservation group in conducting a large-scale ornithological survey in his home district of Coburg, which abutted the German-German border. The survey in itself was an impressive undertaking, with a study area of close to 400 square miles. Nationwide, it was the most thorough ornithological inventory conducted up to that point. And in a move that made the survey even more significant, Kai had decided to include the border strip into the study area.

“And that was of course complete nonsense in a way,” he reflects. “Those were GDR (East German) birds, not Bavarian or West German birds” – meaning that they were flying or perching over East German territory and therefore not in the West German study area. The border fences, as Kai had already noticed, were favorite perches of several bird species during the mating season. The birds could not have cared less whether they were being counted by someone from Bavaria or Thuringia, or that they were perching in the world’s most heavily fortified border, as long as it provided suitable habitat and a chance at finding a mate.

“So I guess I had a gut feeling about it. And the real significance of it is that now we had a comparison: We had an inventory of which species occurred in the “normal” Bavarian landscape, much of which is intensively used agricultural land, and which ones occurred in the border strip,” a landscape that had seen very little human land use for four decades.

And what we found for many of the red-listed bird species was that 90% of their populations occurred in the border strip, and only very small numbers in the rest of the landscape. “We drew attention to these findings in a press conference in 1981, along the lines of “Death Strip as Refuge?”

I am getting more impressed by the minute. I flash back on my own high school career, which in terms of grades was reasonably successful. But quite aside from my inability, at least back then, to tell one bird from another, could I have come up with a research question like this? To compare the incidence of certain bird species in two kinds of landscapes with different land use? How had Kai Frobel been able to do this in his teens? Had he attended a Waldkindergarten – a forest preschool? Had he gotten this understanding of nature from his family?

He laughs.

“Well, my father has always been very interested in natural history. We had field guides for plants and animals around the house; that was probably a bit unusual at the time. So the basic equipment, books and binoculars and so on, my parents always supported that. For many bird enthusiasts, the normal sequence is that you start with the common species and then expand your knowledge to the less common ones, and eventually you get to see some rare ones, maybe even threatened ones. But growing up here next to the border, you practically stumbled onto rare and threatened species.

“And so my volunteer work with the conservation organization BUND Naturschutz was a natural progression from that. In 1979 I did my conscientious objector service at B.N. After that I got my PhD in geo-ecology and starting in 1985, I was working for BN in a professional role, and building relationships and contacts as part of that.

“So we were extremely well prepared when the border opened. But of course we had never expected that that would actually happen. Especially when you’ve grown up here, seeing it every day – on my way to school, 10 km, the road led directly along the border strip – I really thought this monstrous thing is here for eternity.”

Top sign: Green Belt info; Bottom: mine warning

“What was it like for you to grow up with these extremes?” I ask him, “the brutality of the border and at the same time knowing it was a haven for so many creatures? And did you know as a child that there was another Germany behind the border?”

“That there was another Germany I always knew somehow. As to the border… it felt like a situation of extreme tension. On the one hand, these treasures of nature, but with this immediate backdrop of extreme brutality.”

There was a bone-chilling incident during his youth in which heavy rainfall had swept a landmine underneath the border fence into a farm field on the Bavarian side. The mine exploded when the farmer raked it up amid a wad of debris. Kai was present when his father, who was the village doctor, was called to help the severely injured man.

“I had nightmares about the border all through my childhood,” he tells me. “About Soviet tanks coming across the border, things like that. Sometimes at night I could see signal flares over the border strip, sometimes I could hear mine explosions. And even as an 8 or 9-year–old, I somehow understood that we were living right at the seam of a world conflict, and that powerful weapons were close by on both sides. The whole situation was constantly hanging over us, and I always had a queasy feeling when I walked near the border.”

But the more he became fascinated with birds, the more he did walk near the border, and that’s how he knew that the whinchats[2]used the border fence as a prop for their courtship dance, and would occasionally even land in the mine fields. And on a few occasions, he had even stepped across the borderline, as I would soon find out.

“Do you know of other people who spent time so close to the border, or who noticed any of this?” I ask him.

“Mostly the border guards. Some of them had an interest in biology and told me about their observations – only those on the western side; the East German guards were prohibited from speaking to anyone on the western side.

“Well and of course there were times when the GDR border guards would check me out with their binoculars. I’d have binoculars, too, and I’d be wearing a green parka and green rubber boots – because that makes sense for birding, but it probably looked kind of military to them.

“The western guards all knew who I was – ‘Oh, that’s the doctor’s son, he’s looking for rare birds’. But there was one place where they seemed to get suspicious of me. I had noticed that a pair of European nightjars was nesting in a particular place. Those are birds that hunt insects and they breed on the ground; they need sandy open areas. They are almost impossible to see; the only way to detect them is by the sound they make during their courtship dance– sort of a purring sound, like a soft R-R-R-R – which they do at night. So at this place, where I knew that the nightjars were nesting, the federal border guards stopped me several times and asked for ID. I thought that was really strange since they knew who I was and what I was doing. And it wasn’t until after the border opened that I found out what this was about: Very close to the nightjars’ nesting place there had been a tunnel under the border – an inofficial crossing point where the GDR would let secret agents pass between its territory and West Germany. And the federal border guards thought that I was hanging around there because I had something to do with that. I also found out that they had a file about me at their headquarters.”

“So both Germanys had a file about you?” I ask.

“That’s right,” he confirms matter-of-factly.

We both finish our coffee and walk out into the street to climb into his VW.

* * *

Kai is driving on the overgrown double-track of the Kolonnenweg now, the border guards’ patrol route. He points back across the valley.

“Those houses on that hillside over there, that’s where I grew up. It’s less than a kilometer from here to there. So it was easy to ride my bicycle over here.

“These fields were here back then, too – a field on the Thuringian side, a field on the Bavarian side, with the border strip in between that was left largely to its own devices. Right here it was actually quite narrow, only about 40 meters. And right over there a farmer has planted corn right in the Green Belt; that’s a gap of 200 meters. The farmers on the western side were quick after the border opened in 1989, some leased or purchased land on the Thuringian side, sometimes for unbelievably low prices because their eastern colleagues had no experience with western land values.”

And sometimes farmers would simply plow a bit farther into the Niemandsland, which of course was not truly no one’s land but GDR territory, and after Unification, the newly united Federal Republic of Germany’s territory. “That was of course completely illegal,” Kai says. “In the early 90s, the Green Belt suffered major losses in this way.”

“Would you say that that was the greatest challenge in protecting the Green Belt?” I ask.

“No,” he tells me, “the single biggest challenge was the Mauergrundstücksgesetz in 1996 – the law regarding border property. This law stated two things: One, that those whose property in the border had been expropriated by the GDR would be able to buy it back at 25% of market rate, and two, that any remaining properties in the former border should be sold off on the open real estate market. More than 60 million euros [USD 85 million] — would have been needed to buy the land, which was way beyond any available conservation budgets. And all the environment ministers [of Germany’s federal states] were actually supporting the Green Belt, but the finance ministers were against it, because their ministries would have benefited from the sale.

“Angela Merkel was the environment minister for the federal government at the time. She had spoken vehemently in support of the Green Belt, but she had to inform us that “it was not possible to give consideration to the Green Belt under the Mauergrundstückgesetzbecause it is not a matter of public concern.”

I am surprised. Even if the full extent of the Green Belt’s significance for biodiversity was not known in 1996, I thought that its meaning as a landscape of remembrance would have been easily apparent and that that alone would be seen as a matter of public concern. Maybe even as a symbol of unity, or the aspiration towards unity. How many countries get a chance at having such a unique national monument?

It would take another twelve years of lobbying by Kai and his BUND colleagues, and a new federal government, for this view to win out. In 2008 the Mauergrundstücksgesetz was reversed.

“What happened to the people who had been expropriated?” I ask.

“Those who had applied while the law was in effect were able to buy their land back. So about one third of the Green Belt is in private ownership. Most of the owners are actually quite supportive of the Green Belt.”

Stay tuned for Part 3!

I am so enjoying your posts! Keep them coming!!

Great Elise – you bet!

This story is such an inspiration on many levels. Such a lovely example of living one’s passion from early on, and how something so awful turns into something so positive.Thanks for making this available and known, Kerstin!

So glad you are enjoying this Julie!

Kerstin this reminds me so much of the work I did in upstate NY in the Adirondacks for five summers (2002-, with the second Audubon/ NYDEC/ Cornell Bird Breeding Atlas that tracked breeding habits during a 5 year process and published it every 20 years. It was in the mid 2000s. And I counted loons returning to breed there as well.

Wonderful work.

Hi Lucy, that’s great to hear that you have an Adirondack connection and were part of the Breeding Bird Atlas! I consider myself fortunate to live right in between the Green Mountains and the ADKs. – I have participated in Vermont’s loon count myself several times. Being out on a lake and hearing that otherworldly laugh/cry is one of the experiences I treasure most in life.

Oh yay , it is indeed great to know you know what I’m talking about. !!! I must send you some of my loon photos, as I became friends with the now head of the B

And just an FYI but I’m sure you must know this already.

https://nyti.ms/3nirzEP

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/02/world/europe/germany-reunification-berlin-wall.html

I’m sure you’ve seen this , right? Coincidence? LOL

I did see it! Excellent article, even though I had hoped they would let me write it – but it makes sense for them to ask their own Berlin correspondent…

Excellent, Kerstin, a beautiful article that evokes the drama and tension of the times as well as the sense that nature can continue to show us a way forward.