Today’s post explores how “our everyday lives are criss-crossed by border zones” (anthropologist Renato Rosaldo) and how not only physical but also social borders shape our identities. Find out what the late anthropologist Daphne Berdahl had to say about this and how she came to settle in Kella for her field work shortly after Reunification in 1990. (See previous post for how I connected with her good friend Anna, who took me around Kella and shared her reflections on life in the East German borderland.)

Anna pulled out from the parking area at Braunrode, the spot that had once served as a viewpoint from which West Germans could wave to their loved ones in Kella. As we entered the village, I noticed a prominent crucifix on the side of the road: a reminder that we had re-entered not only Thuringia but also the predominantly Catholic Eichsfeld region. Both Kella and the Eichsfeld had been part of various borderlands – regional, religious, territorial, and national – for centuries. Before becoming the border between East and West Germany, the boundary line on which Kella sits had delineated Hesse from Prussia, and later from Thuringia, and the Eichsfeld from a variety of Protestant states and principalities.

Not surprisingly, as Daphne Berdahl had observed, this history of multi-layered and changing boundaries has shaped the village’s social landscape and perhaps even its residents’ sense of identity. To her, border zones presented a particularly fruitful way of thinking about societies, identity, and the concept of culture. She cites another anthropologist, Renato Rosaldo (1989):

“More than we usually care to think, our everyday lives are criss-crossed by border zones, pockets and eruptions of all kinds. Social borders frequently become salient around such lines as sexual orientation, gender, class, race, ethnicity, nationality, age, politics, dress, food, or taste.”

Berdahl then adds:

“In many respects, this view of borderlands and border zones offers a particularly compelling way of conceptualizing identity and social life. Such an approach not only highlights the processual, fluid, and multi-dimensional aspects of identity but also stresses how identities are contextually defined, constructed, and articulated.”

In a way, Anna came to exemplify for me someone with a fluid yet grounded sense of identity: someone able to transcend societal boundaries without losing her sense of self. On the one hand, she clearly had a deep connection to the Catholic church and faith. At the same time, the state socialism of the GDR – which was adamantly atheist – had been the socioeconomic “air” she had breathed for the first twenty-five years of her life: a context she experienced as a given because she had been born into it and it was part and parcel of her Heimat. Things that grated on older villagers, like the constant identity checks at the Schutzstreifen checkpoint (the 500 meter zone along the border, referred to as “protective zone” in GDR lingo) and the unpredictable and often sparse supply of goods in the village store – the Konsum – were easier for her to bear:

“I was born into it; I didn’t know it any other way,” she explained. At the same time, the lessons imparted by her teachers about the evils of capitalism and the imperialist West had, to some extent, also become part of her worldview. She told me of the one time she and her husband Erhard had been allowed to cross the border, in 1988, for an aunt’s 60th birthday. As they traveled through West Germany by train, Andreas had exclaimed “The grass really is greener here!” by which he meant that the cars were fancier and the building facades cleaner than those in the GDR. Anna, with the remarkable honesty I came to appreciate so much about her, told me that “even if the grass had been greener, I would not have admitted it, out of principle!” because of the allegiance she felt to her home country, the GDR.

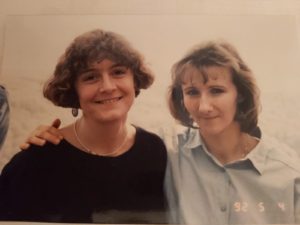

However, the state indoctrination had not been able to throttle her human instincts, most notably with Daphne who, as an American, would have been considered a Klassenfeind (class enemy) by the GDR. Granted, the physical border had been gone for a year by the time she appeared in Anna’s office unannounced one December evening in 1990. But its social and psychological dimensions – the phantom border – would not disappear so fast, as I had come to learn even from my distant Vermont life, and as Daphne herself had observed during her time in Kella.

Anna was the first person Daphne encountered in Kella that day on her search of a Schutzstreifen village for her doctoral research. She had tried several other villages already but had not been able to find accommodations for herself and her husband in any of them: Because new construction had been heavily restricted in the “protective zone” during GDR times, families were making do with whatever living space they had had before the restrictions had been imposed. Many lived with several generations under one roof and simply had no room to spare.

Two auspicious circumstances helped Daphne find the one vacant apartment in Kella that December: Anna, who was employed by the mayor’s office at the time, was working late that evening, and because Anna knew everyone in the village, she also knew that an elderly woman had recently died. The fact that Daphne spoke good German probably helped her case, but there must also have been a spark between the two women during that first conversation, an impression that only grew during my conversations with Anna. In any case, Anna contacted the mayor, the mayor contacted the recently deceased woman’s family, and the path was clear for Daphne and her husband John to rent the vacant apartment

In next week’s post, find out how Kella’s pilgrimage chapel ended up in the border strip, in plain sight but out of reach for the villagers for 28 years.

I can’t wait to read more!

Great, please do! Now there is more for you to read 🙂