Sorry about the gap in postings – I am learning that blogging while biking is quite a challenge! I am now taking a week or so to catch up and process the experiences and encounters of the last couple of weeks, so you should be seeing more updates in the days to come. Thanks for your interest and patience!

Picking up where I left off last time…

The weather forecast and the ominous wind last night hold true: As soon as I return from a breakfast visit to the nearby bakery, the rain sets in. No matter, I wanted to visit the monastery anyway… maybe the rain will stop by the time I am done…

The weather forecast and the ominous wind last night hold true: As soon as I return from a breakfast visit to the nearby bakery, the rain sets in. No matter, I wanted to visit the monastery anyway… maybe the rain will stop by the time I am done…

In contrast to the ruins of the church I had seen last night, there is actually quite a bit left of the monastery: The cloister (where a concert series takes place each summer – unfortunately no concert is scheduled while I am here) the cloister garden, a small chapel, a work and study area for the monks, and a rather spacious tower that now holds exhibits about the monastery’s history.

I take in what I can; then decide to ask the woman at the front desk about the border. She looks to be in her 40’s, which makes her old enough to have experienced it. There are no other visitors at the moment and she obliges me. She tells me that she grew up a little ways north of here, in a small town in the Harz mountains in what was then West Germany. The border was quite close to her parents’ house and she always knew that it was there, but did not understand the scope of what it meant. She remembers that sometimes during quiet nights, she could hear the dogs bark in the border strip, not knowing that they were kept there to go after people trying to flee from East Germany. Asked about how the region has fared since reunification, she says that there is more competition for jobs in the area now, since there is still a pay differential between the eastern and western federal states and jobs in, for example, geriatric nursing pay more in western states like Lower Saxony than in Thuringia, across the former border. She offers this observation in a matter-of-fact way, not as a complaint – she sees reunification as a good thing that happened and a process that is still getting sorted out.

When I step out of the monastery it is still raining, so I climb into my rain gear and start pedaling. My next destination is the nearby town of Bad Sachsa, one of several spa towns in the Harz mountains but with the special attraction (for me) of a Grenzlandmuseum (borderland museum). I have to watch the path because it is getting muddy from the rain, but I do manage to look up and see one of the ponds that the monks created many centuries ago. I think this is the one where swimming is permitted, but I am drenched already – so I forgo the opportunity and push on through the mud.

When I step out of the monastery it is still raining, so I climb into my rain gear and start pedaling. My next destination is the nearby town of Bad Sachsa, one of several spa towns in the Harz mountains but with the special attraction (for me) of a Grenzlandmuseum (borderland museum). I have to watch the path because it is getting muddy from the rain, but I do manage to look up and see one of the ponds that the monks created many centuries ago. I think this is the one where swimming is permitted, but I am drenched already – so I forgo the opportunity and push on through the mud.

I generally don’t get too excited about large-scale human interventions in the landscape, and I realize that “large scale” is a relative term. But these ponds do speak to the monks’ ingenuity, since they managed not only to contain water in the porous karst landscape and to support a growing human population and mining industry, but inadvertently also created bird habitat that much later helped bring about protection as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site.

I had called ahead to the borderland museum and found out that Herr P., a former (East German) border guard is working there today. When I arrive, he is in the middle of giving a tour to other visitors – this gives me time to dig into my bike panniers, find dry clothes, and retreat to the museum’s bathroom to change.

I glom onto Herr P.’s next tour, in which he gives an animated commentary on the museum’s exhibits, which cover the border itself, the developments leading to the division of Germany, changes in the border regime and in the relationship between the two German states during the time of the division, and escapes from East Germany. Rather than attempt to summarize all of this, I have a hunch that it would be more useful to give a description of the border itself. (I will fill in more historical background as I go, but feel free to ask questions in the Comments section if you ever feel lost.)

The first thing to understand is that the border between East and West Germany was not a line or a wall, but a strip of land filled with various kinds of obstacles (Actually the very first thing is that when I talk about the border between East and West Germany, I am NOT talking about the Berlin Wall – but you have probably figured this out by now! The Berlin Wall was also not just a wall, but a strip of land. The two are related and both were deadly, but geographically different).

The diagram below shows the border strip from the West. In the diagram,  the border itself is indicated by the black-and-yellow post just behind the dashed black line – meaning that the western fence (in some places, a wall) was still on East German territory. For someone approaching from the east (once they had made it through the 5 km exclusion zone and the 500 m protective strip), the first thing they would see was a tall signal fence or, in areas near towns or villages, a wall. Floodlights were located in regular intervals along it, and if touched, wires along the fence would transmit a signal to the watch towers, alerting the border guards that there was a likely border breach in progress.

the border itself is indicated by the black-and-yellow post just behind the dashed black line – meaning that the western fence (in some places, a wall) was still on East German territory. For someone approaching from the east (once they had made it through the 5 km exclusion zone and the 500 m protective strip), the first thing they would see was a tall signal fence or, in areas near towns or villages, a wall. Floodlights were located in regular intervals along it, and if touched, wires along the fence would transmit a signal to the watch towers, alerting the border guards that there was a likely border breach in progress.

In between the two fences or walls, there were, depending on a given location, any or all of the following obstacles: Dog runs, concrete vehicle ditches, wooden or steel contraptions designed to stop vehicles and entangle people on foot, mine fields, and trip wires. Next to the western wall or fence was a 10 m strip of land that was meticulously raked each day to ensure that tracks of anyone fleeing would be clearly visible. Next to that were concrete tracks for patrol vehicles. Perhaps the most pernicious obstacles of all were the scatter mines, which were installed over 440 km of the border from1971 into the early 1980s. These mines were attached in three layers on the inside of the western fence and triggered when one of three wires was touched.

Back to the area between the western fence and the actual border: Since this was still East German territory, you were still not safe if you had actually made it this far alive (coming from the east), or accidentally stepped over the (invisible) line from the west. East German border guards had special openings in the fence to patrol this strip of land and were instructed to use their firearms against people trying to flee.

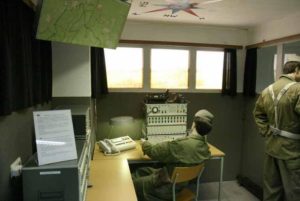

One of the museum’s prized exhibits is a reconstruction of a border guard command station; absolutely authentic as Herr P. assures us. I ask him whether he was ever on duty during an attempted escape. He explains that he was a “Grenzaufklärer” (border investigator) and was only called in after an escape had taken place or been attempted, to reconstruct how exactly it had been done. I don’t press the issue, but try to imagine what it must have been like to do duty along this border. Emotionally taxing is probably putting it mildly.

We are joined by the exhibition director, Herr O., who had served in the West German army and was familiar with the border from that side. He became interested in what became of the border a few years ago when his son asked him what was left of it and whether one could hike along it to the Baltic Sea.

By now it is late afternoon and I still have a good 30 km in front of me… in the rain, as a quick look outside confirms. I thank the two and embark on a wet ride. When I arrive at my modest hotel drenched to the bones for the second time today, the owner takes pity and pours me an extra-generous glass of wine. Ahh…I end the day with gratitude for random acts of kindness.

This is great! I love travelling with you through the day. Why was Herr P. a border guard? Was that mandatory or voluntary service? I’m wondering what he feels about the border today. Keep pedaling and writing!

Hi Emilie, so glad you are traveling with me through the day! Border service was voluntary, at least after 1973. When I asked Herr P. how he came to be a border guard/investigator, he told me that he was from a small town in the 500 m Schutzstreifen/protective zone. Because of the added restrictions on residents in that zone, there were few options for work, and because his whole family was there, he wanted to stay there. He also mentioned that border guards received additional pay and some other special benefits, and that he was therefore able to provide for his family quite well. He seemed happy that the border is gone, though I wasn’t able to question him in great detail about that since it was getting near closing time and we were talking about so many things…

Thanks for the extra info. I’m always curious about the personal stories and the rear-view-mirror reflections arrive upon with the benefit of distance from an event.

Thank you for another thought-filled entry, Kerstin.

Your conversation with the woman at the monastery left me with a question: is competition for work also great on the eastern side of the border or does that side in fact suffer from a lack of qualified workers because such people have taken up employment on the western side given that, if I understand, wages are higher there? If this is so, what is the impact of this on life on the eastern side? This sort of “brain drain” is a problem in Romania, medical professionals, for example, having departed in droves for Western European countries since the 1989 revolution because of the greater financial security, but their departure is to the detriment of people in Romania.

I also have a question about the scatter mines: I gather these have all been removed or are they still around and, if so, do the sorts of accidents that take place in underdeveloped countries where mines have been laid occur when people come across them by accident?

Good luck with the next phase of your venture.

Hugs,

Gerard

Hi Gerard,

the brain drain and wage differential you describe for Romania has definitely also been an issue for eastern Germany. In fact, I had been half expecting to hear about this, as well as the higher rates of unemployment, from the people I spoke to on the eastern side of the former border – until I realized that they had all lived within the Schutzstreifen (the 500 m protective zone) and were so glad to be rid of the restrictions that it was easier for them to put everything else in perspective. This is my interpretation, of course, and based on only a few conversations so far. I hope to address all of this in more depth in the pre-arranged interviews I plan to conduct later.

As to the scatter mines: In this particular post, I was referring to the “Selbstschussanlagen” (self-detonating devices or directional antipersonnel mines), 60,000 of which were installed on the western fence along parts of the border. They were all removed in 1983/4. However, there were also land mines (over a million to my knowledge) placed along mine fields within the border strip. A thorough effort to remove and defuse them all was conducted after the border was opened in late 1989 and into 1990. I have seen warning signs in some parts of the border urging visitors to stay on designated paths because some mines may have been washed away by rain or be unaccounted for for other reasons. I have not heard of any accidents involving mines in the former border.

I’m enjoying reading your posts, Kerstin. It’s fascinating and chilling to read your description of the layers of security that were around the border.

The reminisces of Herr P and the woman at the monastery are compelling and I look forward to reading more about the people you encounter.

Hi Steve, thank you for reading my blog; I am so glad you find it interesting. The personal encounters and conversations have been compelling indeed; I am barely able to catch up writing about them!

Kerstin,

Another fascinating report. Enjoying your trip immensely.

–Dennis