The former border crossing Duderstadt-Worbis (where the suitcase protest took place in January 1990) is now the site of the borderland museum Eichsfeld. Someone who doesn’t know this could easily cruise by on the smooth B-247 federal highway and have no idea that there was ever a crossing or a border here. I can’t say that I actually remember the place, but I do have a strong feeling that this is where I first crossed the suddenly defunct border about a month after the fall of the Berlin Wall, on a cold December day in 1989. Some friends and I had decided on a whim to drive to the border and see if we could cross without a visa. We were approaching by car from the nearby (western) town of Göttingen, passports in hand, nerves on end.

The former border crossing Duderstadt-Worbis (where the suitcase protest took place in January 1990) is now the site of the borderland museum Eichsfeld. Someone who doesn’t know this could easily cruise by on the smooth B-247 federal highway and have no idea that there was ever a crossing or a border here. I can’t say that I actually remember the place, but I do have a strong feeling that this is where I first crossed the suddenly defunct border about a month after the fall of the Berlin Wall, on a cold December day in 1989. Some friends and I had decided on a whim to drive to the border and see if we could cross without a visa. We were approaching by car from the nearby (western) town of Göttingen, passports in hand, nerves on end.  The whole country was still swept up in an intoxicating mix of euphoria and disbelief about the events of November 9 – the unexpected opening of the Berlin Wall, the reunions of family members and friends who had been kept apart for four decades, and the first glimpses of the respective “other” Germany.

The whole country was still swept up in an intoxicating mix of euphoria and disbelief about the events of November 9 – the unexpected opening of the Berlin Wall, the reunions of family members and friends who had been kept apart for four decades, and the first glimpses of the respective “other” Germany.

During those early days, no one knew what the procedure was at any of the border crossings; much less what would happen with the border and the two German states in the future. As we approached the checkpoint and slowed down, the adrenaline in the car was almost palpable. What happened next was a complete surprise to us: The border guard raised his arm and waved us through. We looked at each other – he did not even ask to see the passports! Was he actually smiling? It was unbelievable. We drove on to the nearest town, parked the car somewhere, and walked to where there seemed to be some kind of event. As it turned out, the event was an open-air Kaffeetrinken (the German ritual of coffee and cake) put on by, it seemed, the whole town for visiting Westerners. Tables laden with baked goods and thermos bottles lined the streets; we were handed steaming mugs of coffee and plates of home-baked cake; people laughed and cried and said “Willkommen,” over and over again.

Even now, I remember the strange mix of familiarity and culture shock. The people here were clearly German, and what was being celebrated by them and the visiting “Wessis” alike was a sense of belonging together. But there was something different about the town from the towns we knew – not entirely different, but the houses were brown from the burning of coal, the air smelled like sulphur, the cars were smaller and goofy-looking, and the stores were called “Konsum” and somehow quaint-looking.

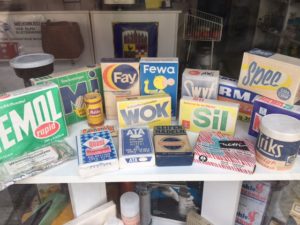

We decided to go inside a “Konsum” and – gawked liked tourists in a far-away exotic place, I am afraid. This store was much smaller than the ones we were used to – though it did spark a flash-back to the corner store of my childhood. The goods and brands were ones we had hardly ever heard

We decided to go inside a “Konsum” and – gawked liked tourists in a far-away exotic place, I am afraid. This store was much smaller than the ones we were used to – though it did spark a flash-back to the corner store of my childhood. The goods and brands were ones we had hardly ever heard  of, and there were fewer choices. Not that anyone needs 45 kinds of cereal or tea or detergent to choose from, but… this was a different world from the one we were used to.

of, and there were fewer choices. Not that anyone needs 45 kinds of cereal or tea or detergent to choose from, but… this was a different world from the one we were used to.

I can only hope that my gawking wasn’t too obvious. Certainly my culture shock was nothing compared to what easterners were in for in the months and years to come. If they didn’t lose their jobs outright in the massive restructuring of the East German economy, many experienced arrogance or condescension from Westerners, who often seemed to have very little patience for the process of adjustment it took to get used to the new Germany.

Just as a side note for now: Reunification – which took place on October 3, 1990 – was not truly a union of two equal entities. What actually took place was more like an adoption of East Germany by West Germany. For many easterners, especially people over 45 or 50, this meant that their entire frame of reference was gone. They had a much harder time getting used to the rules of a market economy, not to mention the subtler cultural differences that had developed between the two Germanys. For younger people, reunification opened up possibilities they could not have dreamed of otherwise. More on all of this as this expedition continues…

A note about the photos: Unfortunately neither of us on that first visit to East Germany had a camera with us. The pictures of the Konsum were taken last week when I encountered one along my expedition. It was no longer functioning as a store, but served as a museum. Again, something to contemplate about the experience of East Germans in the process of reunification and since…

The pictures are helpful to understand the simplicity of existence in the east! Happy travels!

Hi Kerstin,

It was truly gripping reading about your first entry into the former DDR – I sat on the edge of my seat. But what a wonderful reception! I was curious to learn whether you had interactions of any depth with locals on that occasion; I am guessing perhaps not given the very public nature of the Kaffeetrinken, but if you did and you recall their content, it would be very interesting to learn about them.

“Konsum” as a name for a store in the DDR reminded me of the store names in Romania during the socialist period, some evidence of which still lingers on signage here and there. Stores selling produce were called “Legume si Fructe” or “Vegetables and Fruits” and stores with bread were “Piine.” The lack of commercialization indicated by this is meaningful, needless to say, and so different from a capitalist market economy in certain ways although the U.S. does often have domination by a single name and hence corporation – e.g., Starbucks – rather than by a basic need and hence the state.

Your entry also provoked memories of another feature of stores under socialism in Romania: goods were kept behind counters, requiring people to stand in line to purchase them, and access was not always certain, especially in some regions of the country during the austere 1980s. People working in the “Alimentara” were consequently quite powerful, the reverse of what prevails in a capitalist society, where the customer comes first. I am wondering whether it was also the case in the DDR that access to consumables was somewhat ordered in a similar fashion.

Look forward to more. Enjoy your adventures and writing. Hugs, Gerard

Hi Gerard, thank you for providing these parallels from Romania, and sorry about my late reply (but I know you were also traveling ;-).

Regarding your first question, I don’t remember any in-depth conversations with residents of that town; it was quite a throng of people and we pretty much just got swept along. I imagine that people who lived closer to the border on the west and/or who had personal ties (e.g. with relatives) across the border had quite a different experience. I know of several (usually small) towns that had been separated by the border where the residents of one town visited the other and vice versa, often with marching bands, choirs, and presents. In one town I visited, this first impromptu visit after the border opened in late 1989 turned into an annual celebration on October 3 (the Day of German Unity).

Regarding goods that were kept behind counters: Yes, there was an equivalent in the DDR, referred to as “Bückware” (bücken = to stoop), but this did not apply to all goods – maybe because in East Germany, the supply of food and goods was generally quite a bit better than in other East Bloc nations – though quite unpredictable. At any given time, there might have been a large supply of (for example) toilet paper in one town, but due to distribution problems, no toilet paper at all in the next. Often people would just buy something that was available in order to be prepared for the next shortage of that item. I have heard that most homes had impressive amounts of bed linen even though (or because) bed linen was rarely available in the stores.

Your point about the respective power of sellers vs customers in capitalist vs planned economies is very – powerful.

Hugs,

Kerstin

[…] here for my memories of my own first crossing to the “other Germany” after the fall of the […]