Anna had reserved a room for me in a small Gasthaus one village over from Kella. During GDR times, Pfaffschwende had been just outside the Schutzstreifen, the high-security “protective zone”. The narrow road to Pfaffschwende had been the only one by which Kella residents could access the rest of the GDR. As she and Andreas drove me to the Gasthaus, Anna pointed out the spot where the checkpoint had been.

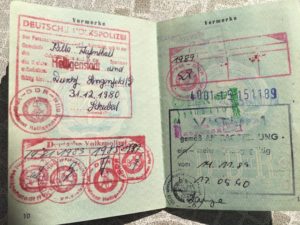

“My classmates and I had to pass this checkpoint every day, twice a day, and of course we had to always remember to have our IDs with us,” she said. Kella was too small to have its own school, so all the children from Kella were taken by bus to the school in Pfaffschwende. On the way home from school “you had to be careful to get on the right bus,” Anna said matter-of-factly: without the official stamp in their papers, the students from outside the Schutzstreifenwould not have been allowed past the checkpoint.

For the same reason, inviting friends from “outside” to visit her at home was out of the question. What about when kids got older, though, I wondered? What if you really liked someone and wanted to spend more time with each other?

“A daughter is not a family member”

Anna and Andreas had experience with that, too. They had always liked each other, but at some point they began to really like each other. Because Andreas was from a village on the other side of Pfaffschwende, outside the Schutzstreifen, Anna’s home in Kella was off-limits to him. Without first-degree relatives in the Schutzstreifen, he was not eligible for a visitor permit. Even when Anna became pregnant, he was only issued a temporary permit – one that expired the day before their daughter was born. When he applied for an extension in person at the district office in Heiligenstadt, he was told that “a daughter is not a family member” – because he and Anna were not yet married. The soft-spoken Andreas was so annoyed with this response that he went straight to the Staatsrat (one of the GDR’s constituent governing organs) in Berlin to plead his case. Shortly afterward, the district office gave him a permit. “I’m sure the Staatsrat called up the local party bureaucrats and said, leave us alone with your local B.S.,” he said with a grin.

Despite the restrictions on travel even close to home – or perhaps because of them – Andreas had developed an impressive knowledge of far away places: He had collected and studied maps for as long as he could remember. In conversations with Daphne, before he had ever been able to visit the U.S., he could tell her from memory not only which interstate highways would get her from one city to another, but also which states she would traverse and which cites she would pass.

“Wasn’t it difficult to get your hands on maps of the western world, though?” I asked him. But Andreas had found a way. “I knew a bookseller in Heiligenstadt who would save me maps whenever new ones arrived.” Regarding actual travel, he said “I would have loved to travel – and I would have wanted to come back home.”

I felt reminded of my conversations with Silke and Britta Kowalski. There it was again, that strong connection with their Heimat of people in this vexing borderland.

Kerstin, Another lovely story that brings the borderlands alive! Imagine being told that a daughter was not family. I applaud the courage of the people and what they had to overcome.

Another fascinating story from the border region. People doing their best to live full lives in what must have been a very difficult situation.